What beliefs drive parents to engage in intrusive parenting practices?

Parents play a critical role in fostering (or hindering) their children’s motivation to achieve. When parents step in to help their children only when they need it, children can thrive. But when parents “helicopter,” or intervene excessively, children may persist less at difficult tasks and struggle to problem solve independently.

This raises an interesting question: if “helicoptering” can have such a negative impact, what drives parents to do it in the first place? For example, why might a parent take over and do a school project for their child instead of simply giving them hints or letting them work independently?

To answer this question, I conducted a series of studies in collaboration with Drs. Ellen Markman and Carol Dweck at Stanford University. We specifically wondered whether helicopter parenting might be driven, at least for some, by a belief that parents must intervene and do things on behalf of their children if they want their children to succeed. This is a belief that has increasingly come up in popular media in recent years (as an example, see this New York Times article titled, The Bad News about Helicopter Parenting: It Works.

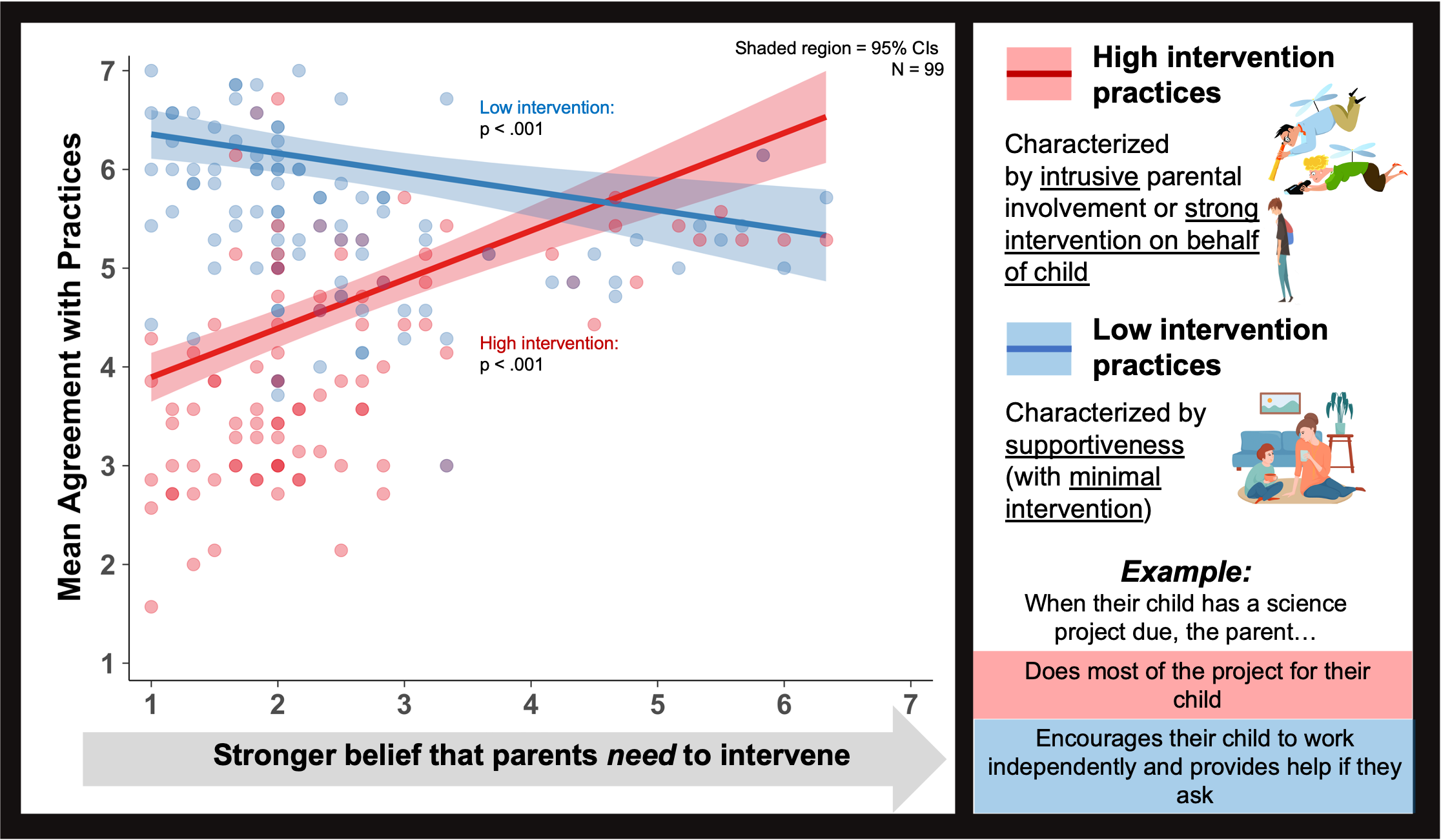

In a pre-registered study, we explored whether parents who believe that they need to intervene might be especially prone to agreeing with and actually engaging in helicoptering practices.

We found that the more parents believed that they need to intervene to make decisions or solve problems for their children (even by the time their children should be more independent, e.g., during young adulthood), the more they endorsed specific high-intervention, helicoptering practices. They even agreed with practices that have been shown in prior research to reduce motivation (e.g., doing a school project for one’s child).

In follow-up studies, we explored whether parents who believe that they need to intervene to ensure their child’s success would still endorse helicoptering in cases where a child was already excelling academically. Surprisingly, we found that this was in fact the case: these parents believed that high-intervention practices were appropriate regardless of whether a child had consistently performed well or poorly in the past. This robust relationship suggests that parents’ beliefs about the necessity of intervening could be an important target for parental education programs and other efforts aimed at encouraging a more autonomy-supportive parenting approach.