The developmental origins of reputation management

At some point or another, we’ve probably all been concerned wanting to seem ‘smart’ in the eyes of others. By adulthood, we learn that we aren’t alone in feeling this way: we recognize that others can (and often do) experience similar worries. We also learn that these worries can influence how someone engages with the world. For instance, we realize that someone who wants to seem smart might shy away from answering questions when they’re not confident or from seeking out help when they’re struggling to understand something.

But when do we come to understand that reputational concerns can have this kind of impact on others’ behavior? To answer this question, I conducted a series of studies in collaboration with Dr. Alex Shaw at the University of Chicago. We specifically were curious to understand when children begin to recognize that a desire to appear smart might shape how someone acts around other people.

Across five studies, we recruited a total of 576 four- to nine-year-old children to answer this question. We specifically chose this age range because prior research suggests that this is when children themselves begin engaging in some forms of reputation management, such as shifting their behavior in response to different audiences. However, just because children engage in reputation management themselves doesn’t mean that they necessarily have an explicit understanding of the fact that others do it, too. We wanted to know when children could begin to predict that someone with reputational motives will behave differently than someone without such motives.

We investigated this by telling our child participants a story about two kids: an intrinsically motivated kid who cares about being smart, and a reputationally motivated kid who cares about appearing smart to others. We then asked them to make predictions about which story character they thought would engage in a particular behavior (e.g., lying to a classmate about having done poorly on a test).

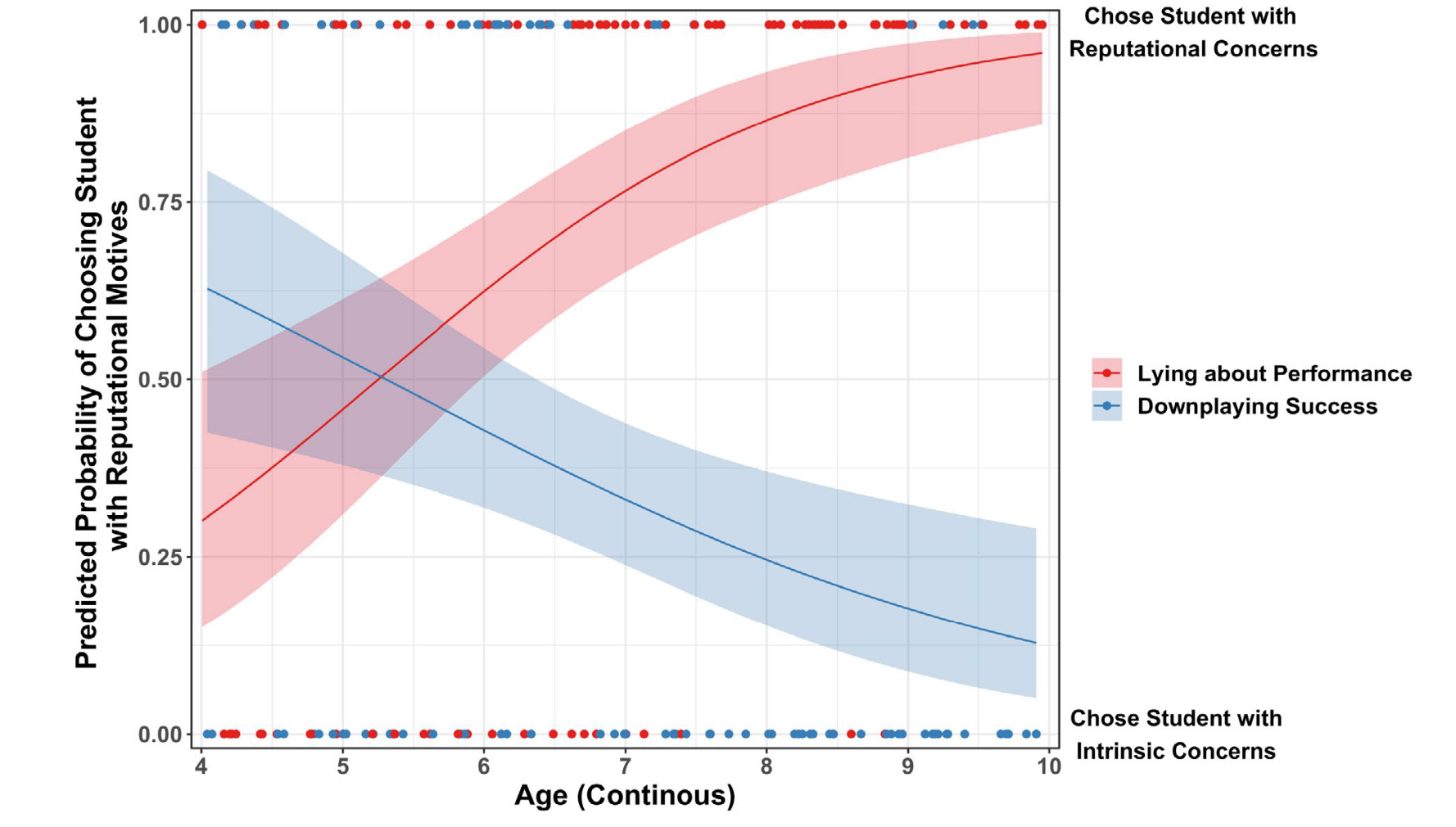

We found that, with age, children predicted the reputationally motivated child would be more likely to lie to cover up failure (p < .001) but less likely to downplay success (p = .003; see below).

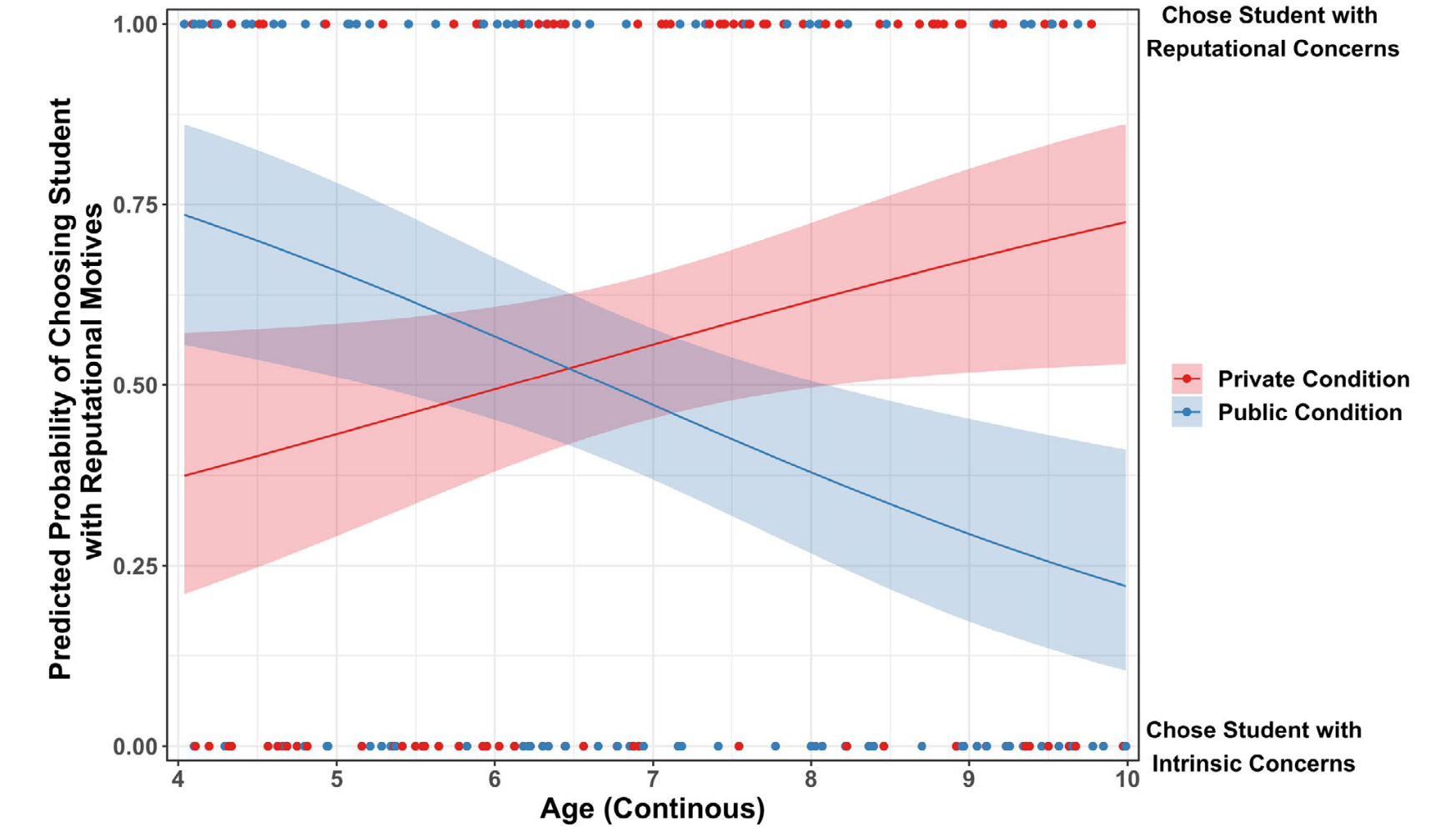

We also found that, with age, children thought that the reputationally motivated child would be less likely to seek help in public (where classmates could see them) than in private (p < .001).

Taken together, our findings suggest that, as children get older, they better able to recognize how reputational concerns about appearing smart to others might influence someone’s behavior. It was around age 7 in particular that most of these predictions began to emerge. This suggests that, by the first grade, children know what kinds of actions (e.g., seeking help publicly) might make people think they are less smart. We discussed the potential implications of these findings for education in a recent Scientific American piece.

You can also find a full-write up of these results in our Child Development paper.